Ewa Dzięgiel

The Periodisation of the Polish-language Press in the Soviet Ukraine in the 1920s and the 1930s

Contents:

1. The years of 1918–21/22

The only time after 1917 in Ukraine when Polish-language press, representing non-communist political options, was published, was the stage of armed fights and of the still non-established Soviet power, lasting until 1920. The most significant title issued in Polish in Kiev since 1906, i.e. "Dziennik Kijowski" [The Kiev Journal] (the releases of 1915–17 are available at: Digital Library of Wielkopolska), was closed in 1919, and its polygraphic base has been used by the "Komunista Polski" [Polish Communist] created after the Red Army has occupied Kiev. This periodical, having changed its name into "Głos Komunisty" [The Voice of Communist], was the most important Polish-language title in Ukraine until 1922. The non-communist periodicals "Głos Podola" [The Voice of Podolia], "Lud Polski" [The Polish People], "Ziemia Podolska" [The Podolian Land], were still issued in 1920, in the city of Kamieniec Podolski [Kamianets-Podilskyi], far-distant from Kiev (Skydan 2010, further literature there). It was possible, because from November 1919 to July 1920, the city stayed within the Polish administrative authority.

Press published in the Soviet Ukraine, similarly to other Soviet republics, was of political nature, subordinated to the central government. Particularly, intense propaganda work has been performed through the publishing of Polish-language periodicals during two periods of time. One was related to the establishment of the Ukrainian authorities, i.e. the war against the Symon Petliura Ukrainian troops and the Russian anti-communist "white" army led by General Anton Denikin, and the Polish-Bolshevik (Polish-Russian) war of 1919–1921. The second one was linked to the fight for the common collectivisation of agriculture initialised in 1929. Both of these periods of time have been marked by the publishing of a dozen or so Polish-language titles in Ukraine.

The longest published periodical of the war period – "Głos Komunisty" – appeared in Kiev in March 1919. The forerunner of this title was "Komunista Polski", issued in February–March of 1919, right after the city has been occupied by the Red Army. The task of the war agitation was of primary importance at that time, so in the climactic months of the Polish-Bolshevik war in Kiev, one more Polish-language title, under a changed name of "Żołnierz Rewolucji" [Soldier of the Revolution], was issued since July 1920 as a front Red Army newspaper. It has been distributed by the political apparatus of the Red Army, on the other side of the front line, within the agitation among the Polish Army soldiers fighting against the Bolsheviks. The publication of the front newspapers was a priority at that time, thus the Red Army was the privileged publisher. Supplements were edited to the "Głos Komunisty": in 1919 "Głos Armii Czerwonej" [The Voice of the Red Army] (5 issues), and in June–July of 1920 the "Bulletin of the »Głos Komunisty«” in the form of a poster (18 issues). "Głos Komunisty", in March 1922, was transformed from a journal into a weekly magazine, and the last issue appeared in May 1922.

The communist titles of the war period were generally issued for a short amount of time, and the one published for the longest period of time, was the mentioned "Głos Komunisty", issued in 1919–1922. The largest publishing activity has been related to the agitation during the Polish-Bolshevik war (1919–20). The title "Wiadomości Komisarjatu" [The News of the Precinct] published in 1918 is a bibliographic curio – supposedly, there has been only one issue (Daszkiewicz 1966, 88). It was supposed to be the organ of the ephemeral Soviet republic under the name of Donetsk-Krivoy Rog Soviet Republic (Russian: Донецко-Криворожская советская республика, Ukrainian: Донецько-Криворізька Радянська Республіка), with its capital in Kharkov (February–March 1918). In 1919, a title "Komuna" [Commune] (Odessa) was issued as an organ of the Communist Party of Poland, and additionally, "Sztandar Komunizmu" [The Banner of Communism] (Kharkov/Kiev). "Na Barykady" [Onto the Barricades] (Kharkov), published in 1920, was a soldier periodical, related to the Warsaw Revolutionary Red Regimen (Russian: Революционный Красный Варшавский Полк), formed in 1918 as an origin of the Polish formation in the Red Army. In 1920, a weekly magazine "Przegląd Komunistyczny" [Communist Review] (Kharkov/Kiev) was additionally created, distinctive from other front newspapers. In 1921, there was just the Kiev title "Głos Komunisty" and the Kharkov "Na Barykady" transformed into "Komunista" [The Communist]. A biweekly magazine "Młody Towarzysz" [The Young Comrade], whose first issue appeared in Kiev in 1921, has been addressed to the youth.

Famous names of Polish communist activists, born and educated in Poland, such as the columnist Julian Leszczyński-Leński, aside from Feliks Kon, Henryk Politur, Bolesław Skarbek-Szacki, can be found among the editors and authors of that time.

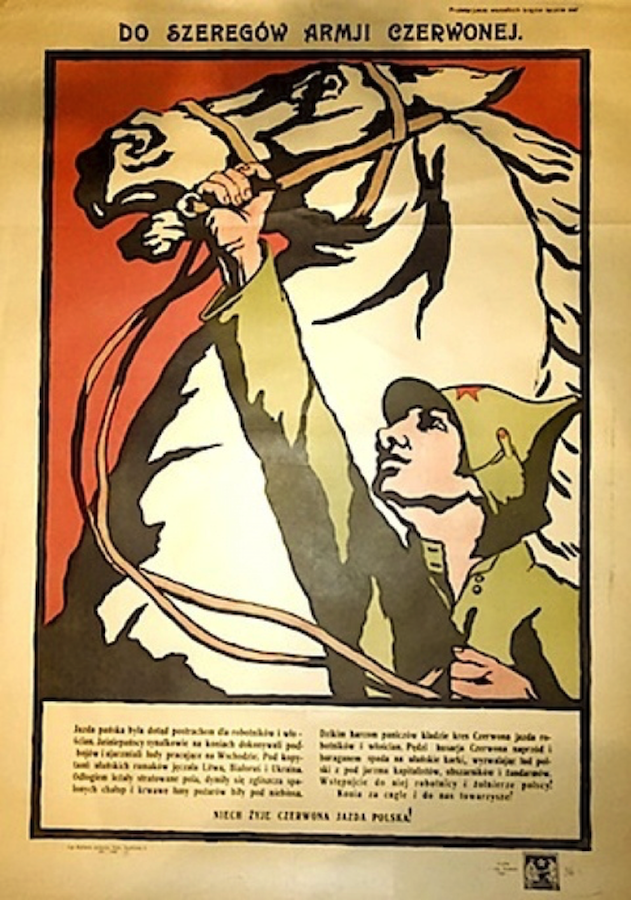

The papers published in 1918–22 were distinguished not by the number of the titles issued simultaneously, because most of them were printed shortly (the number of issues did not exceed 30, generally several or between ten and twenty issues), but by the high circulations of a couple of them – the front line periodicals. The circulation of several Polish-language front line papers was record-breaking, achieving the maximum amounts in the summer of 1920. Never in the subsequent decades, until the II World War, has the Polish-language periodicals in Ukraine exceed that level. The maximum single circulation of "Głos Komunisty" was 15 thousand copies in 1920 (Ślisz 1958, 105; Daszkiewicz 1966, 93), and that of the "Żołnierz Polski" [Polish Soldier] was 20 thousand (Daszkiewicz 1966, 93). The circulation of the "Żołnierz Rewolucji" may be estimated on the basis of a report supplied in "Przegląd Komunistyczny" (1920/3, p.7) – the 3 issues published in August (issue numbers 2–4) had a total circulation of almost 90 thousand, so the one-off circulation might have reached 30 thousand copies. Information on the Polish-language publishing houses, including the circulation of press and other propaganda materials, such as brochures, appeals, posters, agitation postcards, was submitted in August in the mentioned "Przegląd Komunistyczny" (1920/3, p.7). This issue informs that during that month, over 173 thousand copies of "Głos Komunisty" were issued altogether, almost 90 thousand copies of "Żołnierz Rewolucji", more than 127 thousand copies of brochures, and almost 272 thousand copies of appeals and agitation postcards. The author also presents the planned circulation of the publishing houses, but supposedly, it has not been fulfilled. He also informs that the artistic column has been organised, and that there is a couple of posters in the press. An example of such poster, published in Kiev in 1920 in the circulation of 10 thousand copies, is the illustration of a red peasant and a workman killing the Polish white eagle. The illustration is accompanied by a Polish-language text.

|

Illustration 1. A Soviet propaganda poster, artist unknown, Kiev 1920. Inscription: "In the clutches of the white eagle cried the proletariat of Poland, Belarus and Ukraine. Today, the workpeople of countries and towns free themselves from the shackles of slavery and exploitation. Under the hits of the working class hammers, Poland of capitalists and gendarmes falls into debris, the white eagle dies. Under the red banner – a new POLISH SOVIET SOCIALIST REPUBLIC – wakes up to life. LONG LIVE THE REVOLUTION!" Source: http://redavantgarde.com |

|

Illustration 2. A Soviet propaganda poster, author: Boris Silkin (Vasilevich), Kiev 1920. Inscription: "To the ranks of Red Army / Long Live The Red Polish Cavalry". Source: http://redavantgarde.com |

The actions of the soviet propaganda during the Polish-Bolshevik war were very intense, and the Polish side reacted to it, so there was a peculiar "poster fight" (Leinwand 1992, 1993). The posters played an essential role in the visual propaganda, particularly when a significant part of the recipients on the territory of Ukraine were illiterates.

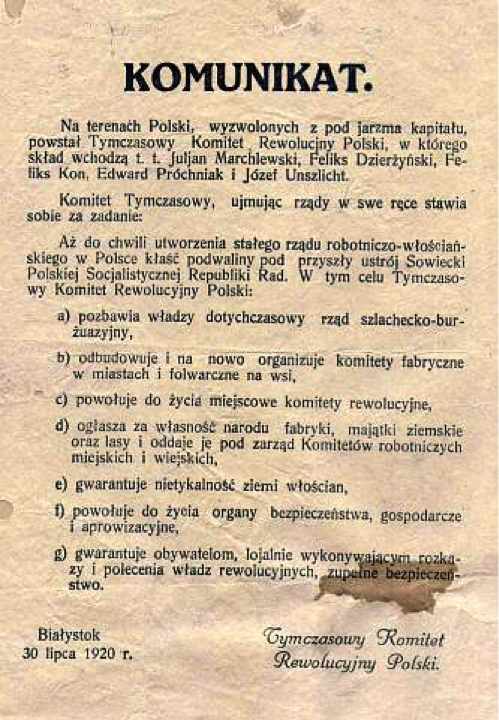

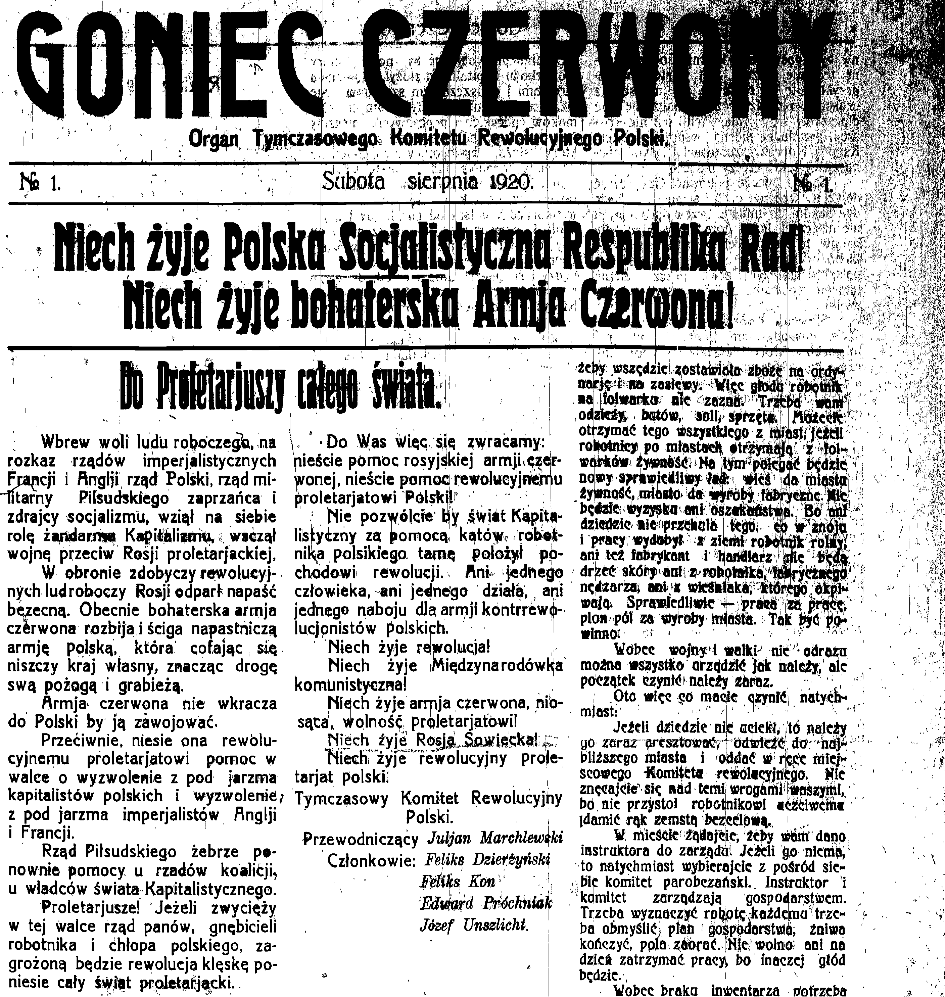

In July 1920, a Provisional Polish Revolutionary Committee (Polrewkom, Russian: Польревком) was formed under the leadership of Julian Marchlewski and Feliks Dzierżyński. It was a type of puppet government for the planned Polish Soviet Socialist Republic. The members of the Polrewkom included, among others, Feliks Kon – a collaborator of the titles under discussion. A part of the Polrewkom activists (Feliks Dzierżyński, Julian Marchlewski, Feliks Kon) travelled on a special train, right behind the soviet army marching to the capital of Poland, preparing for the seizure of power.

|

Illustration 3. Polrewkom, early August 1920. In the middle: Feliks Dzierżyński (middle row 2. from the left), next to him Julian Marchlewski, Feliks Kon and Józef Unszlicht. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/ File:Polrewkom_1920.jpg |

|

Illustration 4. A statement released by Polrewkom, 1920. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/ File:Tkrp manifest.jpg |

The soviet propaganda in 1920, inter alia, put force on the perspective of establishing the Polish Soviet Socialist Republic, following the Red Army’s occupation of Warsaw. A vision of a "red" Warsaw emerged in the context of the red terror (with a positive connotation) as a seat of the Head Revolutionary Tribunal of the Polish Soviet Socialist Republic ("Biuletyn »Głosu Komunisty«" 1920/2). In the "Przegląd Komunistyczny" dated September 1920 (already after the Bolsheviks lost the Battle of Warsaw), Jan Wojtyga wrote about the activity of Polrewkom, closing the article with the sentence: "When the wave of proletarian revolution builds up in Poland, then it shall flow within the circuits marked by the Provisional Polish Revolutionary Committee" (1920/3, p. 4).

|

Illustration 5. A piece of the front page of the 1 issue of "Goniec Czerwony" [The Red Messenger] – the organ of Polrewkom. Source: http://pbc.biaman.pl/dlibra/publication?id=22245 |

As a result of the Polish victory in the Battle of Warsaw (August 13–25, 1920) and the counter-offensive of the Polish army, the Red Army has been repulsed. In October 1920, a ceasefire has been agreed in Riga, and in March 1921, a peace treaty establishing the course of the borders.

|

Chart 1. A list of titles of 1918–22 with schematic chronology |

|

|

Source: own study; Daszkiewicz 1966. |

2. The years of 1922–29

In 1922, the most popular, and the longest published title in Ukraine "Sierp" [Sickle] (1922–35), started to appear. It was the main Polish-language periodical in Ukraine – an organ of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine (Bolsheviks). It was published on the republican level, mostly in Kiev, with exception of the years 1930–33, when the editorial board was moved to Kharkov. In the years 1922–28, "Sierp" appeared as a weekly periodical, and then, two times a week and more often. The title played an essential propagandist and organisational role with respect to the Polish minority in Ukraine. "Sierp" confirmed its profile – a periodical addressed to the rural community – by publishing an agricultural guide in separated divisions, starting from the very first issues until 1929: Agricultural economy and Agricultural guide. The main contents of the title were the informative-propagandist texts, fulfilling the current tasks defined by the authorities. "Sierp" also supervised the network of correspondents, who acted a particular role of communist activists on site and informers, in the soviet regime. The denunciations submitted by them to the newspaper played an essential role in the process of population control (see: Political Background).

Famous communist activists and men of letters, such as Konstanty Wiszniewski, Henryk Politur, Jan Teodor, Bolesław Skarbek-Szacki, have been associated with this title. Some of them were arrested during Stalin's purges in the 1930s, and lost their lives.

As demonstrated by this title, it is possible to track the changeable fate of both the Polish journalists, writers, communist activists, as well as Polish periodicals. Within 13 years of functioning, the editorial board, and the writing formula, have been changing. The transformations have been related to the changes in the soviet policy, including the policy towards national minorities.

The needs of the communist propaganda among children and young people were to be realised by the titles issued on the republican level in Kiev and Kharkov. A monthly magazine "Młody Towarzysz", addressed to youngest children, better known under a changed title of "Sztandar Pioniera" [The Pioneer's Banner] (1924–25), was created in 1924. Furthermore, in the years of 1929–1935, a journal "Bądź Gotów!" [Be Ready!] was issued. The educational tasks also included the brake–away of young Poles from the traditions of the Polish culture, shaping the Soviet Pole, who identifies himself with the USSR. With reference to the patriotic poem by Władysław Bełza with the incipit: Kto ty jesteś [Who are you]? Polak mały [Little Pole], "Sztandar Pioniera" published a piece, with the opening lines of: "Kto ty jesteś [Who are you]? Pionier Mały [Little Pioneer]! / Aż się wścieka burżuj biały, / Gdy mnie ujrzy, bowiem czuje, / Iż ja zgubę mu gotuję. [There the white bourgeois gets mad, / When he sees me, as he feels, / That I am preparing destruction for him]. / [...] Gińcie więc burżuje biali! [So die, white bourgeois!]” (1925/8, p. 3–4).

Created in 1925 in Kiev, "Głos Młodzieży" [The Voice of Youth] – an organ of the young communist organisation (komsomol), was addressed at young people. It was, apart from "Sierp", the most known Polish-language title, published for over a decade (1925–1935). "Głos Młodzieży" focused the literary circles of "young" authors of Polish origin, who started to publish their pieces in the assigned "Stroniczka Literacka" [A Literary Page] appearing in 1927–29 (among others Władysław Grabowski, Paweł Świszcz, Kazimierz Śliwiński). Krystyna Sierocka (1968, 210 passim) characterises the writing of this group, as compared to the literary writing of the "old" men of letters. The ancestry of the "young" has had a substantial influence on their artistic attitude. Contrary to the writers of the older generation (migrant, educated in the traditions of Polish culture), the "young" were the alumni of the Soviet schools, komsomol and party organisations. They have presented their artistic programme in the introduction to the volume of poetry, published in 1927 by "Głos Młodzieży". This is what they have written about the top principles: "Skry – is not a signature of the author, it is not a soulless fencing with the round phrases, the efflorescence of form and style. All of the poems included in the volume reflect the social life, and their authors first and foremost try to serve the question of the revolution. There we notice the feelings of the Polish youth, brought out with great earnestness and enthusiasm, the changes, which they experience in life. Deep understanding and the perception of a new life prevails in them, whether in the factory, on the field by the plough, or in the barracks of the Red Army. And most importantly, «our youngest ones» – watchfully follow the development of political affairs and they vividly react to them in their poems" (Skry. The volume of poetry, Kiev 1927, p. VI–VII, cf.: Sierocka 1968, 249). The poetry of the youth, especially in the beginnings, also published in "Głos Młodzieży", did not present a high artistic level (Sierocka 1968, 251–2). On the other hand, the most known writers from the older generation (migrant one), such as Bruno Jasieński, Stanisław Ryszard Stande, Witold Wandurski, Henryk Drzewiecki, did not live through the Stalin's repressions of the 1930s, they have all been executed.

A teaching and political aid for educators, especially in the teaching of adults (in likneps), was the journal "Do Światła" [Towards the Light] – with a subtitle: "Gazeta dla małopiśmiennych" [Newspaper for the illiterates], the six issues of which appeared in 1927–28.

|

Chart 2. A list of titles established between 1922 and 1929 with schematic chronology |

|

|

Source: own study; Daszkiewicz 1966. |

Since the mid 1920s, another way of press activity develops, i.e. the wall newspapers are organised. These are hand-written or type-written texts, prepared in one copy, pinned up in workplaces, seats of the organisations, clubs, schools, often in the so-called red corners (Lenin corners). The action of the wall newspaper creation and the factory, company, university newspapers (Russian: многотиражки), served the activation of the groups of workers to the socialist competition and the current control of the outcomes of work (Lenoe 2004, 146; Nérard 2008, 50).

The central Polish-language newspapers insistently popularised the creation of the wall newspapers. "Sierp", in 1925, organised a contest and an exhibition of the best wall newspapers. Among the 67 submitted newspapers, 3 written by adults and 3 school–pioneer ones have been awarded (1925/29, p. 3). The shortcomings of the wall newspaper content have been summarised – including the "redundancy of political articles" and the "unapproachable language". A guide of how to publish a wall newspaper has also been included, describing in detail the technical aspects (the volume, the layout, the calligraphy), the contents (essential facts and conclusions, without broad clichés) and style (attractive headlines, clear propaganda slogans, comprehensible language). Further texts in different titles very often criticise the low standard of the wall newspapers (e.g. "Bolszewicka Zmiana" [The Bolshevik Change] 1933/13, p. 2).

Publicising the action of posting wall newspapers in Polish initially gave modest results – 14 wall newspapers, including mainly school-based ones – 9, apart from that 3 working-class ones (in factories) and 2 peasant ones ("Sierp"/1928/4, pp. 6–7) functioned in 1928 in Marchlewsk raion, i.e. in the center of Polrajon.

A variation of the wall newspapers and the factory newspapers were field newspapers (polówki [fields]). The correspondents and the editing offices of polówki have been presented with economic and political tasks of initialising the "socialist competition and storming between the brigades and particular kolkhoz workers", and the "increase of class vigilance" as well as unmasking "the survivors of the class enemies" ("Kolektywista Emelczyńszczyzny" [Collectivist of the Emelczyńszczyzna] 1935/73, p. 4).

3. The years of 1930–39

In the early 1930s, a propagandist effort among the Polish rural people has been intensified, by establishing several local papers and numerous Polish-language supplements to the Ukrainian titles. This was related to Stalin's initiation of the compulsory collectivisation of farms and fighting the peasants' resistance. The second period was between 1930 and 1935, after the initial period of gaining power (1918–21), which was distinguished by the tightening of the propaganda and setting in of so many Polish-language titles. The main slogan of that time was the acceleration of collectivisation. The well-off peasant, referred to as kulak was considered to be the internal enemy.

The newspapers were published as organs of the regional or town Ukrainian Communist Party Committee (Bolsheviks). They were of modest volume – usually 2 pages – and a non-variable set of subjects. The on-site reports of correspondents played the leading role, they focused on the pace of the current rural and industrial campaign implementation, stigmatising the workplaces, kolkhozes and individual people delaying the works. Furthermore, strictly political writings – resolutions of the central and local authorities, reports of the state leaders, have been published. The subject of the continuously repeating columns, such as In fascist Poland, is the news from Poland devoted to the poverty and the proletariat struggle. Poland is described with a number of evaluative denotations, mostly – faszystowska ‘fascist’, burżuazyjna ‘bourgeois’, pańska ‘upper-class’, biała ‘white’.

Establishing and running the local newspapers was entrusted to the communist activists with no journalistic experience, and biographical information is available only about very few of them (Zygmunt Tutakowski, Stanisław Maj). The language of the newspapers reflects the deficiencies in writing technique of the editors and authors, and a large number of mistakes results from the application of calques from Ukrainian or Russian. The most linguistically poor are "Kolektywista Emelczyńszczyzny", "Bolszewik Olewszczyzny" [Bolshevik of Olewszczyzna] and "Sztandar Socjalizmu" [The Banner of Socialism]. The regional newspapers refer, with their formulation, to the interventionist wall newspapers. Reproduced (circulation of 250 to 4000 copies) and distributed on-site, they reached a larger number of readers. Printing Polish-language inserts (semi-inserts) or supplements to the Ukrainian-language titles, or to the greater Polish-language titles, was an additional reinforcement of the propaganda. Frequently, the supplements were addressed to a specified reader, e.g. the youth. A magazine-handbook "Młodociany Szturmowiec" [Juvenile Stormtrooper], published in Kharkov in 1931–32, was intended as a teaching aid for schools with Polish language.

In as far as in the mid-1933, the Committee of the Ukraine Central Communist Party (Bolsheviks) approved the guidelines on the development of the Polish-language press, including the transformation of the Ukrainian-language newspapers supplements into stand-alone titles, but in the early 1935, it issued a decision about the liquidation of half of them, and until October that year – of all of them (Kupczak 2001). All the local titles established in the early 1930s were closed after the end of collectivisation in Ukraine in 1935, when its usefulness has dissipated. Apart from that, in 1935, Polish-language periodicals in Ukraine were eliminated altogether, including the most known ones – "Sierp" and "Głos Młodzieży".

1935 was, in fact, also the end of the publishing of Polish-language periodicals, and all of them were cancelled. Created in 1935 in place of the most known newspaper – "Sierp" – a journal "Głos Radziecki" [The Soviet Voice] included mostly the reprints (translations) from the Russian-language press, without any contents related to the Polish minority in Ukraine.

|

Chart 3. A list of titles of 1930–35 with schematic chronology |

|

|

Source: own study; Daszkiewicz 1966. |

Literature

- Daszkiewicz Jarosław, 1966, Prasa polska na Ukrainie Radzieckiej: zarys historyczno-bibliograficzny, "Rocznik Historii Czasopiśmiennictwa Polskiego", t. V, nr 2, s. 84–137.

- Leinwand Aleksandra J., 1992, Bolszewicki plakat propagandowy w okresie wojny polsko-sowieckiej 1920 r., "Studia z dziejów Rosji i Europy Środkowo-Wschodniej", t. 27, s. 75–87.

- Leinwand Aleksandra J., 1993, Polski plakat propagandowy w okresie wojny polsko-sowieckiej (1919–20), "Studia z dziejów Rosji i Europy Środkowo-Wschodniej", t. 28, s. 57–67.

- Lenoe Matthew E., 2004, Closer to the Masses: Stalinist Culture, Social Revolution, and Soviet Newspapers, London.

- Nérard François-Xavier, 2008, 5% prawdy: donos i donosiciele w czasach stalinowskiego terroru, z fr. przeł. Janina Szymańska-Kumaniecka, Warszawa.

- Sierocka Krystyna, 1968, Polonia radziecka, 1917–1939: Z działalności kulturalnej i literackiej, Warszawa.

- Skydan Oleksandr, 2010, Prasa polska w Kamieńcu Podolskim w pierwszej połowie 1920 roku (komunikat), w: Język polski dawnych Kresów wschodnich, t. 4, red. Janusz Rieger i Dorota A. Kowalska, Warszawa, s. 183-196.

- Ślisz Andrzej, 1958, Polska prasa komunistyczna w ZSRR w latach 1917–1927. Cz. 1–2, "Kwartalnik Prasoznawczy";, nr 1/2, s. 99–107; nr 3, s. 61–73.